RED

-

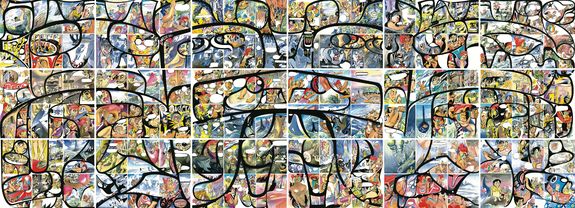

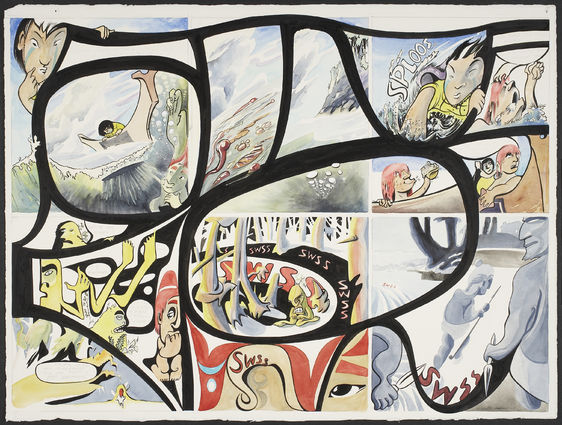

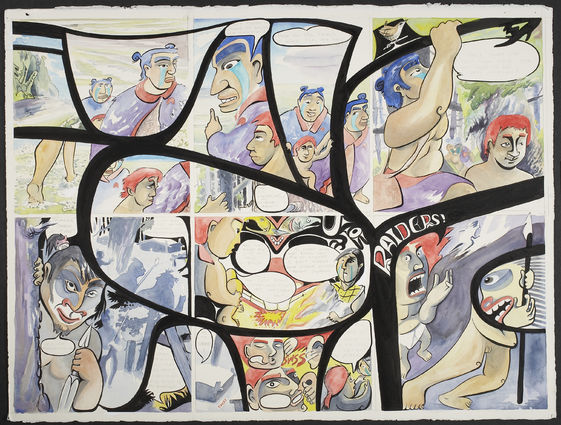

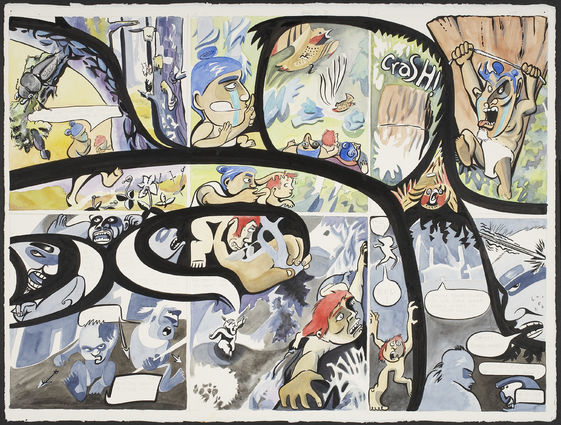

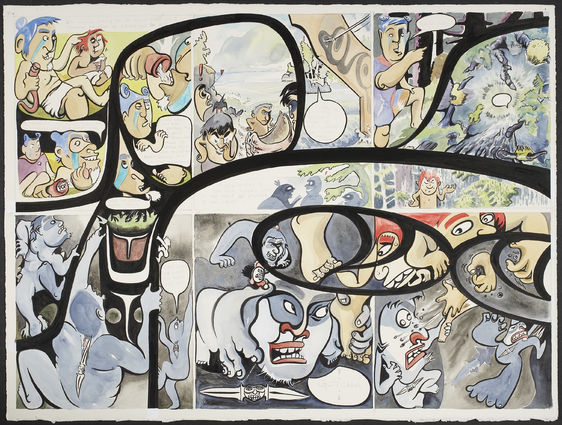

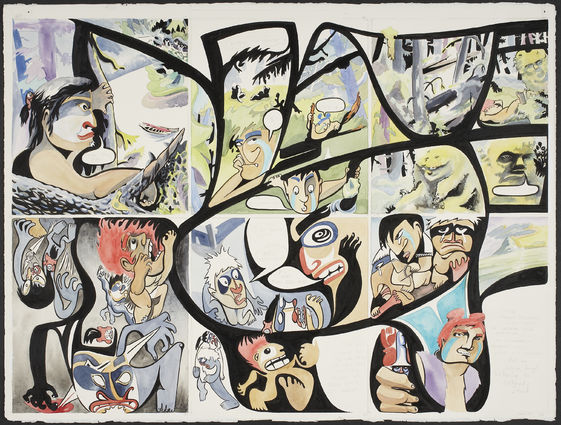

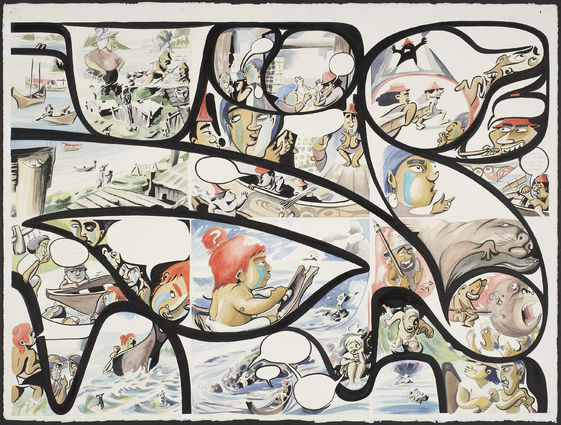

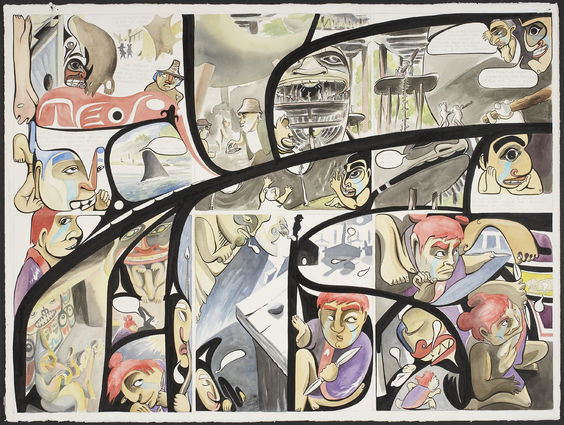

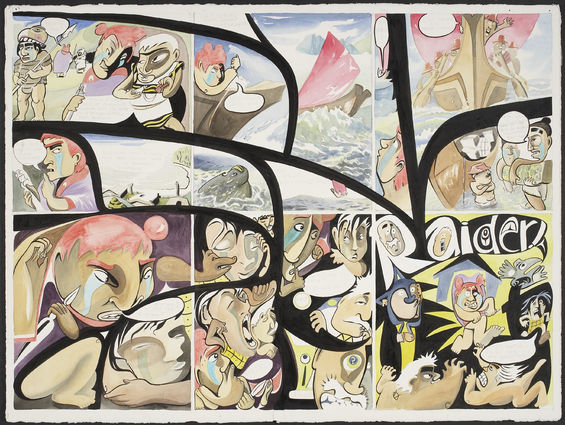

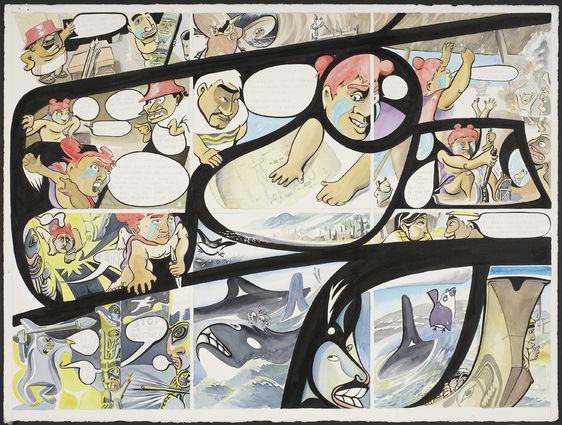

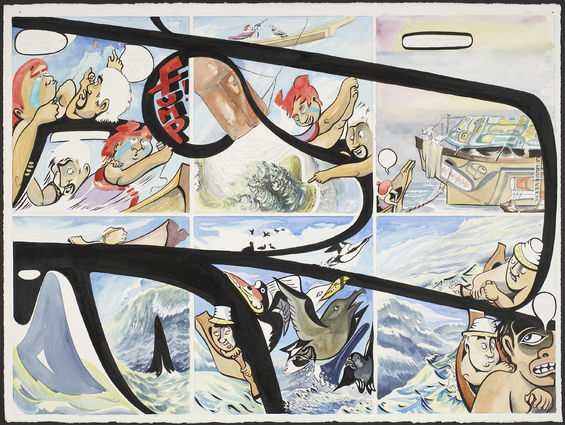

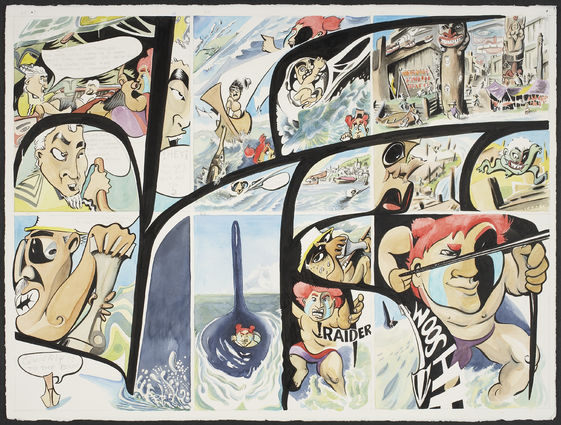

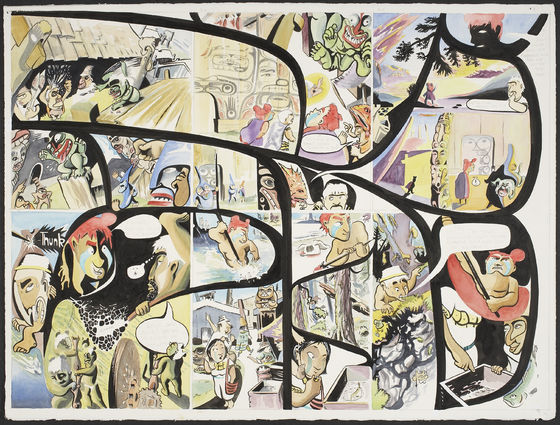

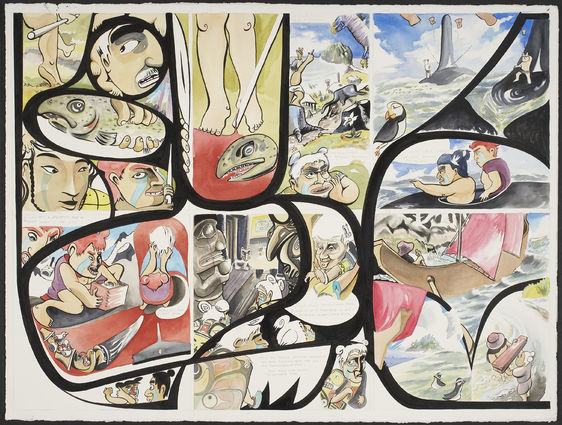

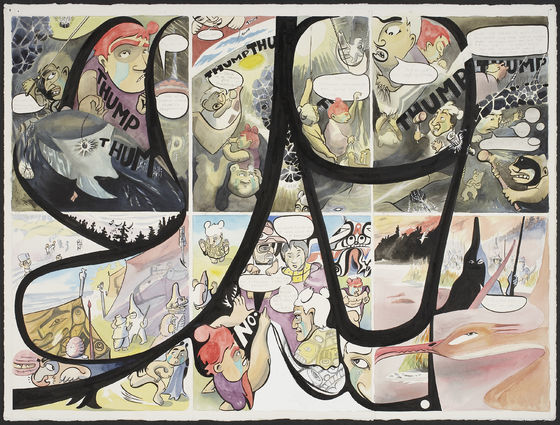

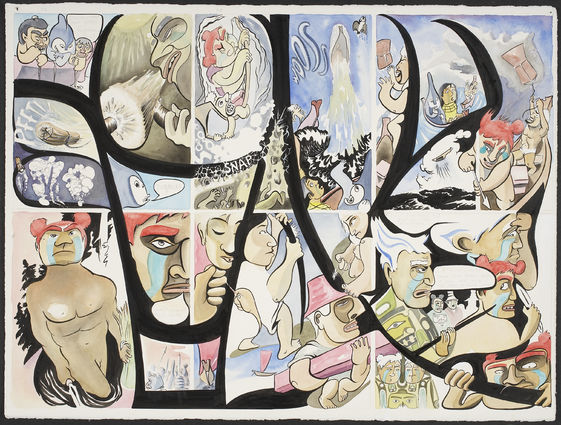

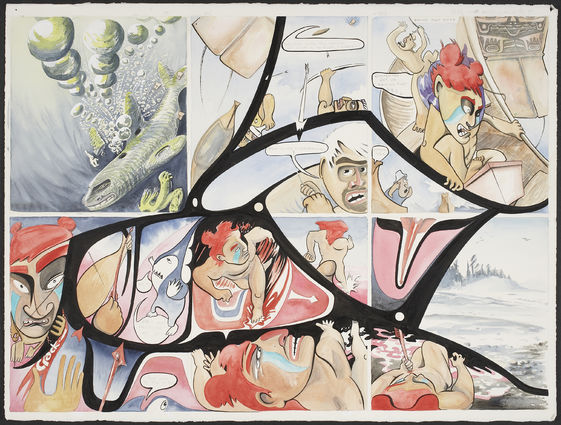

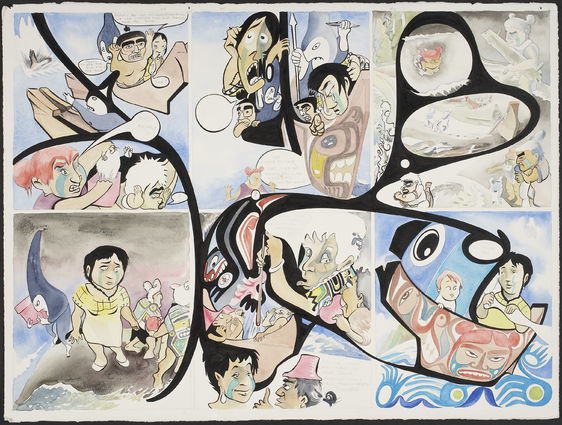

December 25, 2008Watercolour, ink on paper168 x 381 cmUBC Museum of Anthropology, source: Michael O'Brian CollectionRED is the tragic story about a young girl named Jaada and her brother Red. They live together in a village on the west coast of Haida Gwaii. One night, pirates sneak into the village! Red calls out the alarm and everyone flees, but Jaada is captured. Years pass, and Red becomes a chief. He begins to search for his sister...

Editorial Reviews

From Publishers Weekly

The work of an artist from the indigenous people of the North Pacific Canadian islands of Haida Gwaii, this Haida manga intriguingly blends graphic storytelling with a fine art sensibility. The narrative involves the title character's loss of his sister to a party of raiders and the boy's vow to someday find and rescue her, a goal he puts into effect upon becoming the leader of his people. His quest for vengeance results in a series of tragic events that author Yahmagulanaas communicates via an arresting series of images evoking the traditional visual arts of the Haida people. Designed so its pages can be torn out (provided the reader has two copies) and arranged according to a provided layout, the separate pages combine to form a stunning tapestry; when the layout is followed and the book is seen as a cohesive piece of visual art, the story does not fall prey to moments of confusing storytelling that occur when read as a page-by-page work, and the legendary feel of the piece shines through. A unique work with appeal both for those looking for something different in graphic novels, and for those with an interest in the expression of contemporary Native American culture. (Mar.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.From School Library Journal

Grade 7 Up—Red's life is changed forever when his sister is kidnapped by raiders. As years pass and he rises to power in his small village off the coast of British Columbia, he dreams of elaborate scenarios for getting even with the people who took her away from him. When his revenge fantasy is finally fulfilled, it turns out to be both his greatest victory and his tragic downfall. The idea of "Haida manga," an artistic fusion invented by Yahgulanaas, might cause confusion among readers, or at least send them running to Google to find out what "Haida" is. This artistic style, used by the Haida tribe of Native Americans, will be familiar to readers who have seen the stylized faces on totem poles. The bright and colorful artwork is definitely unique, but sometimes it is so overwhelming that it overpowers the story, which might leave readers confused about plot details. "I welcome you to destroy this book" is never something a librarian wants to hear, but that's what Yahgulanaas encourages his readers to do in order to assemble each page into a "formline illustration." It is only when the pages are assembled in this manner that readers will be able to see how every panel connects to other panels and appreciate the true complexity and vision of Yahgulanaas's art. Luckily, this "complete" image is reproduced at the end of the book and inside the dust jacket, so readers should not find it necessary to vandalize more library books than usual.--Andrea Lipinski, New York Public Library

(c) Copyright 2010. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted.From Booklist

The Haida, indigenous to the Pacific Northwest Coast, are known for their seamanship and martial tendencies. Of Haida heritage,Yahgulanaas adapts a piece of his people’s folklore into a pictorial narrative in a manner he calls Haida manga. The story concerns community leader Red, whose childhood trauma—his sister’s disappearance—translates into a thirst for revenge that threatens to lead his people to destruction. But that story is obscured by the surreal, flowing imagery, putatively a product of Haida visual culture, and that obscuring is exacerbated by the thick black lines running through the pages, so that, should one wish to take the book apart, the pages can be put together to create a meta-image. OK, the story is difficult to interpret. But the art offers a glimpse into another culture and effectively captures the malleability of a folktale, its capacity to shift and transform during multiple tellings. For readers interested in anthropological studies, a fine companion to Lat’s Kampung Boy (2006).--Jesse Karp

Media Coverage

- Haida manga: An artist embraces tragedy, beautifully - The Conversation, July 12, 2018

- Fluid Frames: The Hybrid Art of Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas - Art in America, November 2, 2017

- Art Seen: Being serious about play is no joke for Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas - The Vancouver Sun, April 29, 2016

- Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas’s imagery speaks across cultures - The Georgia Straight, April 27, 2016

- The Seriousness of Play by Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas at the Bill Reid Gallery - Hello Vancity, April 24, 2016

- 'Indigenous Beauty': a blockbuster Native American show at SAM - Seattle Times, February 20, 2015